Europe Is Building the Next Tesla. Who Knew?

Nikola’s remarkable rise has relied heavily on European expertise. That raises questions about its valuation and Europe’s failure to find a rival to Tesla.

When Nikola Corp. started trading on Nasdaq in June, the Phoenix-based clean transportation company raced quickly to a valuation of almost $30 billion.

Its market worth has since fallen to a more reasonable $10.5 billion, but that’s still pretty spicy for a business yet to generate any revenue. Its most promising products are its heavy trucks, powered by electric batteries or hydrogen fuel cells.

The rise of Nikola (whose name, cheekily, is another evocation of electrical engineer Nikola Tesla) will have reinforced a view among European auto industry executives that the U.S. stock market operates by different rules. While Tesla Inc. is only modestly profitable, it’s valued at about $275 billion, more than Europe’s five largest carmakers combined.

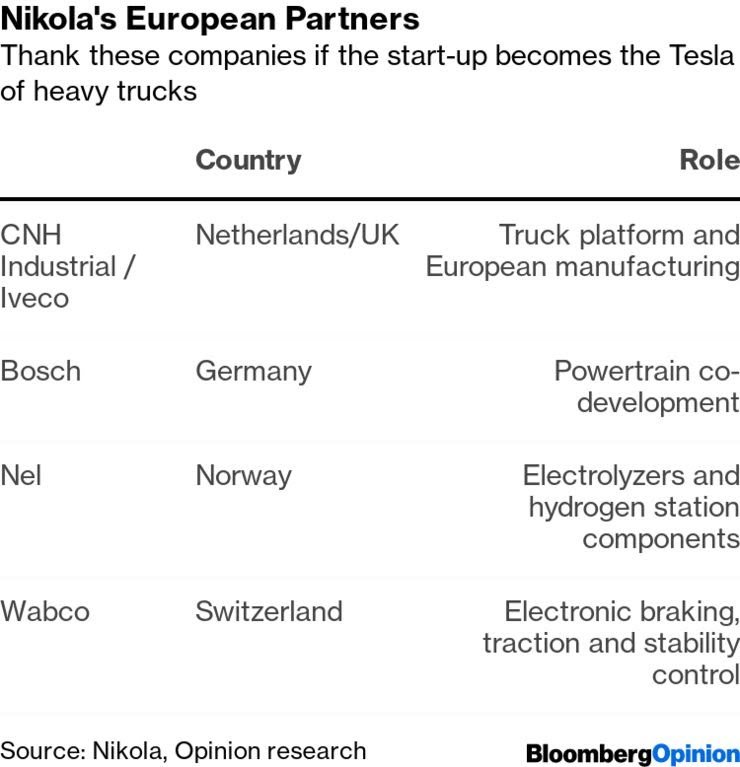

At least Europe has a stake in the latest heavily hyped project. Founded by Trevor Milton, a 38-year-old American college dropout, Nikola is relying heavily on expertise from the old continent. Robert Bosch Gmbh, a German automotive supplier, has helped develop the U.S. company’s electric powertrain, and the first Nikola trucks will be built in a German factory belonging to Italy’s Iveco, a truck maker backed by the billionaire Agnelli family. Bosch and Iveco each own more than 6% of Nikola. CNH Industrial NV, Iveco’s parent, just recorded a $1.5 billion fair value gain on that investment. 1

The biggest question is whether a start-up dependent on so much external help should have a whizzy valuation like Tesla, which builds much of its technology itself. And if Europe has this expertise, why hasn’t it produced its own rival to Elon Musk’s carmaker?

Maybe it’s a lack of chutzpah. Nikola’s name isn’t the only reason it’s often compared with Tesla. Milton’s hyperactive Twitter presence makes Musk look tame by comparison. Both men’s ambitions extend beyond selling zero-emission vehicles to producing and storing clean energy. While Nikola is focused on heavy-duty trucks, it has touted a variety of consumer products including a pickup called the Badger. These are catnip for retail investors, as the excitement over Musk’s Cybertruck demonstrates.

While Tesla and Nikola are both working on electric heavy trucks, they differ in at least two important respects. The first is hydrogen: Musk is dismissive, while Milton thinks hydrogen is the perfect fuel for long truck journeys. The second is their attitude toward building stuff in-house.

True, in its early days Tesla worked with Lotus to help make the Roadster, and Daimler AG helped develop the Model S saloon. Tesla partners with Panasonic to produce battery cells. But Musk is famous for trying to build his own technology, from electric powertrains and automated-driving software to car seats.

Nikola developed its own software, infotainment and battery management-system, as well as vehicle aerodynamics, according to Cowen analyst Jeffrey Osborne. It has outsourced or used hired help to do much of the other stuff. More than 200 Bosch employees were involved in building important parts of Nikola’s trucks, including the electric motor for the axle, the vehicle-control unit, the battery and the hydrogen fuel cell. The result is a mix of intellectual property owned either separately or jointly by Nikola and its suppliers.

There’s no doubt, however, who has the deeper expertise. So far Nikola has been awarded 11 U.S. patents, about 1% of the total Bosch is awarded in a typical year. “Bosch gets paid to help us get to industry standards on products,” Milton told me.

Getting partners to provide the technological building blocks has some advantages. Nikola has only 300 employees and yet its first trucks should start rolling off the production line soon. Working with partners cuts the risk of the manufacturing delays and quality problems that plagued Tesla.

It’s an efficient use of capital too. Nikola’s research and development expenses were just $68 million last year. Tesla spent $1.3 billion. After going public, Nikola has about $900 million of cash, although that won’t go far in the automotive business. For the North American market, Nikola plans to handle its own manufacturing, with technical assistance from Iveco. Nikola broke ground this week on a $600 million factory in Arizona.

Whether or not you believe the extensive involvement of outside partners should have a bearing on its lofty valuation, there are other things that could upset Nikola’s plans.

Building a refueling network is a central part of its business model, but this won’t come cheap at $17 million for each hydrogen station. The company is also entering a competitive field populated by more experienced and better capitalized rivals. Daimler’s Mercedes-Benz failed to follow through on its early experiments with electric cars and let Tesla roar past. It probably won’t make the same mistake with trucks.

Daimler is the world’s largest truck maker and it plans to start production of its electric eActros and eCascadia models next year. The German giant has also formed a joint venture with Sweden’s Volvo AB to develop hydrogen fuel cell systems for heavy vehicles. That venture is valued by the companies at just 1.2 billion euros ($1.4 billion), putting the Nikola valuation into perspective.

Even if its share price looks overblown, Nikola’s improbable rise shows there’s investor demand for clean transportation companies that don’t still have one foot planted in the combustion-engine past. European manufacturers have the technical chops but they must find better ways to capitalize on investor excitement through new business models or spinoffs. Otherwise someone else will.

- This was measured on June 30 when Nikola’s stock was much higher

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.